Portfolio Theory, also known as Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), was developed by Harry Markowitz in the 1950s. It's a fundamental concept in financial economics that deals with the ways in which investors can construct portfolios to maximize expected return based on a given level of market risk.

Risk-Return Trade-Off

- Fundamental Premise: Investors are risk-averse; they prefer a less risky portfolio to a riskier one if both portfolios offer the same expected return.

- Trade-Off: Higher risk is associated with greater probability of higher return and lower risk with a greater probability of smaller return. (하이 리스크 하이 리턴)This trade-off is at the heart of MPT.

Diversification

- Reducing Risk: MPT shows that an investor can reduce portfolio risk simply by holding combinations of different financial instruments, rather than just individual securities.

- Unsystematic vs. Systematic Risk: By diversifying, investors can eliminate unsystematic risk (also known as diversifiable risk or specific risk) related to individual stocks. However, systematic risk (market risk) cannot be diversified away.

- Systematic risk, also known as market risk, refers to the risk inherent to the entire market or market segment. It is contrasted with unsystematic risk, which is specific to a single company or industry. The key reason systematic risk cannot be diversified away is due to its nature and the broad factors that influence it.

- Broad Influences: Systematic risk is influenced by factors that affect the entire economy or large sectors of the market. These include economic recessions, political upheaval, changes in interest rates, natural disasters, and global events like pandemics.

- Impact on All Assets: These factors impact nearly all types of assets - stocks, bonds, real estate, etc. When such broad market shifts occur, they tend to affect the entire market, not just specific stocks or sectors.

- Unsystematic Risk: Diversification is effective in mitigating unsystematic risk, which is specific to individual companies or industries. By holding a variety of assets, you reduce the impact that any one company’s or industry’s downturn can have on your overall portfolio.

- Limit of Diversification: However, when it comes to systematic risk, diversifying across different stocks or sectors isn’t as effective because the factors impacting systematic risk affect almost all companies and industries. For instance, an economic recession will likely lower the earnings potential and stock prices of most companies, regardless of how diverse your portfolio is.

- Correlation in Downturns: During market-wide downturns or crises, the correlation between different types of assets often increases. This means that different assets can start to move in the same direction (typically downwards) together, reducing the benefits of diversification.

- Alternative Strategies: While diversification can’t eliminate systematic risk, investors use other strategies to manage it, such as hedging. Hedging might involve using financial instruments like options or futures to protect against market-wide losses.

- Risk Tolerance: Understanding that systematic risk cannot be diversified away is important for investors in managing expectations and in aligning their portfolios with their risk tolerance and investment horizons.

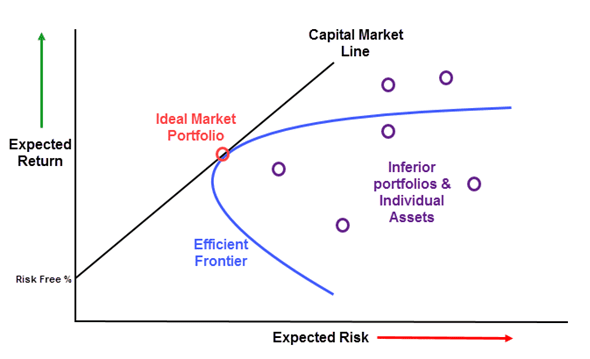

Efficient Frontier

- Concept: The efficient frontier is a graph that shows the optimal portfolio that offers the highest expected return for a defined level of risk or the lowest risk for a given level of expected return.

- Plotting Portfolios: Portfolios that lie below the efficient frontier are considered sub-optimal because they do not provide enough return for the level of risk they carry. Portfolios that cluster to the right of the efficient frontier are also sub-optimal because they have a higher level of risk for the defined rate of return.

Asset Allocation

- Combining Assets: Portfolio theory is not just about choosing the right assets but also about finding the right mix of assets. It involves allocating the portfolio's assets in a way that maximizes return for a given appetite for risk.

- Correlation Between Assets: The correlation coefficient between the asset returns is a critical part of this. If two assets are perfectly correlated, there is no diversification benefit. The goal is to combine assets with low or negative correlations.

- 내 포트폴리오는 correlated한 종목이 많지 않은지 생각해보자!

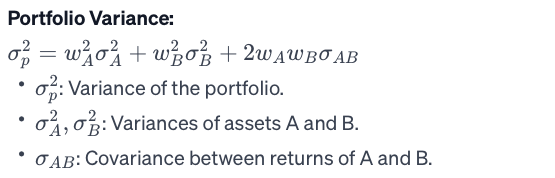

Mathematical Formulation

Let's consider a simple portfolio with two assets, A and B.

- Expected Return: The expected return of the portfolio is calculated as a weighted sum of the individual assets' returns.

- For a single asset, the expected return is typically the average return based on historical data.

- For a portfolio, the expected return is a weighted average of the expected returns of the individual assets, where the weights are the proportions of each asset in the portfolio.

- Portfolio Variance: Portfolio risk (variance) is also a weighted sum, but it includes the covariances between the asset returns. This is where the diversification effect plays a significant role. When assets do not move in perfect sync with each other (i.e., they are not perfectly correlated), the portfolio's overall risk can be reduced.

- Variance and Standard Deviation (Risk):

- The variance and standard deviation of a portfolio represent its risk.

- Variance measures the spread of a set of numbers. In finance, it's used to calculate the dispersion of historical returns of an asset or a portfolio, indicating the degree of investment risk.

- The standard deviation is the square root of the variance and is a more interpretable measure of risk.

- Covariance and Correlation:

- Covariance measures how two stocks move together.

- A positive covariance means the stocks tend to move in the same direction, while a negative covariance means they move in opposite directions.

- Correlation is a standardized form of covariance and ranges between -1 and 1.

- To calculate the correlation coefficient between two assets, A and B, you need to understand the relationship between their returns over a given period. The correlation coefficient (rho) measures the degree to which the returns of the two assets move in relation to each other. +1 Indicates that the returns of A and B move in the same direction at all times, -1 indicates that the returns of A and B move in exactly opposite directions, and 0 indicates no linear relationship between the returns of A and B.

- Efficient Frontier Calculation

- Using these formulas, you can calculate the risk and return for many different possible portfolios. By plotting these portfolios, you can derive the Efficient Frontier, which represents the set of portfolios that offer the maximum expected return for a given level of risk or the minimum risk for a given level of return.

- Limitations and Assumptions: It's important to note that MPT relies on several assumptions (e.g., normal distribution of returns, rational investors) and may have limitations in predicting future performance due to its reliance on historical data

Markowitz's Efficient Portfolio

Harry Markowitz's Efficient Portfolio concept is a cornerstone of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and involves the challenge of creating an 'optimal' portfolio.

- Optimization Problem:

- Objective: The primary goal in Markowitz's framework is to find the best possible combination of assets (portfolio) that offers the highest expected return for a given level of risk, or conversely, the lowest risk for a given level of expected return.

- Portfolio Weights: This involves determining the proportion (weight) of each asset in the portfolio. These weights must sum up to 1 (or 100% if using percentages).

- Risk-Return Trade-off: The core of the optimization is balancing the trade-off between risk and return. Investors usually want high returns but need to manage their risk tolerance.

- Mathematical Methods:

- Quantitative Analysis: This optimization is typically achieved using quantitative methods. The most common approach is to use Mean-Variance Optimization (MVO), a mathematical process that uses the expected returns, variances, and covariances of the assets.

- Efficient Frontier: The result of this optimization is a set of portfolios known as the 'Efficient Frontier'. Portfolios on this frontier offer the maximum expected return for each level of risk.

- Risk Measures:

- Variance or Standard Deviation: Risk in MPT is quantified as the variance (or its square root, the standard deviation) of the portfolio's return, representing the portfolio's volatility.

Real-world constraints are often considered in practical portfolio optimization.

- Transaction Costs:

- Buying/Selling Costs: Every time an asset is bought or sold, there are costs involved, like brokerage fees. Frequent trading increases these costs.

- Impact on Optimization: These costs can significantly affect the portfolio's return and must be factored into the optimization process.

- Taxes:

- Capital Gains and Dividends: Different investments are taxed differently. For example, short-term capital gains might be taxed at a higher rate than long-term gains.

- After-Tax Returns: The optimization should consider these taxes to estimate the after-tax return of the portfolio.

- Regulatory Constraints:

- Investment Restrictions: Certain investors, like pension funds or mutual funds, might have regulatory constraints on what they can invest in.

- Risk Management Rules: There might also be rules about the minimum or maximum amount of certain types of assets.

- Liquidity Requirements:

- Cash Needs: Investors may have liquidity needs that require a portion of the portfolio to be in easily sellable assets.

- Illiquid Investments: Some assets are less liquid and might be difficult or costly to sell quickly.

Practical Implications

For Individual Investors, Portfolio theory suggests the importance of diversifying one’s investment across different asset classes (like stocks, bonds, real estate) and within asset classes (like different sectors or geographies in the stock market). For Fund Managers, Portfolio theory guides the construction of diversified investment funds that cater to different risk-return profiles of investors.

Critiques and Extensions

Some of the key assumptions of MPT, like rational investors and normal distribution of returns, have been criticized. The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and the Black-Litterman model are extensions of MPT, addressing some of its limitations and applying its principles to new areas.

Regardless, despite its limitations and the development of new theories, MPT remains a cornerstone of asset management and financial analysis. In summary, Portfolio Theory provides a systematic approach to constructing investment portfolios that can achieve the best possible balance between risk and return. It emphasizes the importance of diversification and the quantification of risk, and it has significantly influenced the way financial markets and investment strategies are understood and implemented.

댓글